Over the past few months, I have been constantly reading conversations about how Generative AI will reshape software engineering. On LinkedIn, Twitter, or in closed professional groups, engineers and product leaders debate how tools like Cursor, GitHub Copilot, or automated testing frameworks will impact the way software is built and teams are organized.

But the conversation goes beyond just engineering practices. If we zoom out, AI will not only transform the workflows of software teams but also the structure of companies and even the financial models on which they are built. This kind of change feels familiar – it echoes a deeper historical pattern in how science and technology evolve.

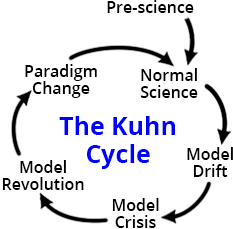

Kuhn’s Cycle of Scientific Revolutions

During my bachelor’s, I read Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn argued that science does not progress in a linear, step-by-step manner. Instead, it moves through cycles of stability and disruption. The Kuhn Cycle1, as reframed by later scholars, breaks this process into several stages:

- Pre-science – A field without consensus; multiple competing ideas.

- Normal Science – A dominant paradigm sets the rules of the game, guiding how problems are solved.

- Model Drift – Anomalies accumulate, and cracks in the model appear.

- Model Crisis – The old framework fails; confidence collapses.

- Model Revolution – New models emerge, challenging the old order.

- Paradigm Change – A new model wins acceptance and becomes the new normal.

The Kuhn Cycle Applied to Software Development

Normal Science

For decades, software engineering has operated under a shared set of practices and beliefs:

- Clean Code & Best Practices – DRY, SOLID, Unit Testing, Peer Reviews.

- Agile & Scrum – Iterative sprints and ceremonies as the “right” way to build products.

- DevOps & CI/CD – Automation of builds, deployments, and testing.

- Organizational Structure – Specialized roles (frontend, backend, QA, DevOps, PM) and a belief that more engineers equals more output.

The underlying assumption is hire more engineers + refine practices → better and quicker software.

Model Drift

Over time, cracks began to show.

- The talent gap – demand for software far outstrips available developers.

- Velocity mismatch – Agile rituals can’t keep pace with market demands.

- Complexity overload – Microservices and massive codebases create systems that are too complex for a single person to comprehend fully.

- Knowledge silos – onboarding takes months, and institutional knowledge remains fragile.

These anomalies signaled that “hire more engineers and improve processes” was no longer a sustainable model.

Model Crisis

The strain became obvious:

- Even tech giants with thousands of engineers struggle with code sprawl and coordination overhead.

- Brooks’ Law bites – adding more people to a project often makes it slower.

- Business pressure grows – leaders demand faster iteration, lower costs, and higher adaptability than human-only teams can deliver.

- Early AI tools, such as GitHub Copilot and ChatGPT, reveal something provocative – machines can generate boilerplate, tests, and documentation in seconds – tasks once thought to be unavoidably human.

This is where many organizations sit today – patching the old paradigm with AI, but without a coherent new model.

Model Revolution

A new way of working begins to take shape. Here are some already visible in experimenting, we can all see around us –

- AI-first engineering – using AI agents for scaffolding code, generating tests, or refactoring large systems. Humans act as curators, reviewers, and high-level designers.

- Smaller, AI-augmented teams

- New roles and workflows – QA shifts toward system-level validation; PMs focus less on ticket grooming and more on problem framing and prompting.

- Org structures evolve – less siloing by specialization, more “AI-augmented full-stack builders.”

- Economics shift – productivity is no longer headcount-driven but iteration-driven. Cost models change when iteration is nearly free.

Paradigm Change

In the coming years, some of the ideas above, and probably additional ideals, could stabilize as the “normal science” of software development and organizational building. But we are not yet there. Once we get there, today’s experiments will feel as obvious as Agile sprints or pull requests do now.

We are in the midst of model drift tipping into crisis, with glimpses of revolution already underway. Kuhn’s lesson is that revolutions are not just about better tools – they’re about shifts in worldview. For AI, the shift might be that companies will no longer be limited by headcount and manual processes but by their ability to ask the right questions, frame the correct problems, and adapt their models of value creation.

We are moving toward a future where the shape of companies, not just their software stacks, will look radically different, and that’s an exciting era to be a part of.