Have you noticed how half the posts on LinkedIn these days feel like they were written by an LLM – too many words for too little substance? Or how product roadmaps suddenly include “AI features” that nobody asked for, just because it sounds good in a pitch deck? Or those meetings where someone suggests “let’s use GPT for this,” when a simple SQL query, an if-statement, or a much simpler ML model would do the job?

Laurence Tratt recently coined the term LLM inflation to describe how humans use LLMs to expand simple ideas into verbose prose, only for others to shrink them back down. That concept got me thinking about a related phenomenon: LLM debt.

LLM debt is the growing cost of misusing LLMs — by adding them where they don’t belong and neglecting them where they could help.

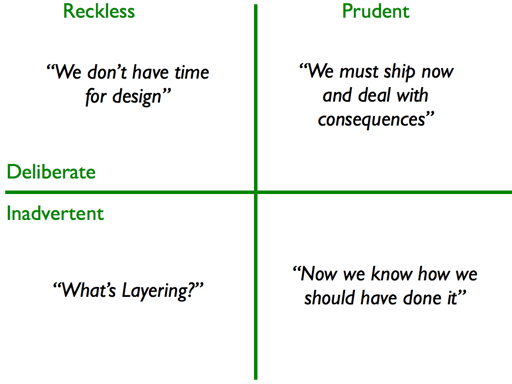

We’re all familiar with technical debt, product debt, and design debt1 — the shortcuts or missed opportunities that slow us down over time. Similarly, organizations are quietly accumulating LLM debt.

So, what does LLM debt look like in practice? It’s a double-edged liability:

- Overuse: Integrating LLMs where they’re unnecessary adds latency, complexity, cost, and stochasticity to systems that could be simpler, faster, and more reliable without them. For example, sending every API request through a multimillion-parameter model when a simple regex or deterministic logic would suffice.

- Underuse: Failing to adopt LLM-based tools where they could genuinely help results in wasted effort and missed opportunities. Think of teams manually triaging support tickets, writing repetitive documentation, or analyzing text data by hand when an LLM could automate much of the work.

Like product or technical debt, a small amount of LLM debt can be strategic: it allows experimentation, faster prototyping, or proof-of-concept development. However, left unmanaged, it compounds, creating systems that are over-engineered in some areas and under-leveraged in others, which slows product evolution and innovation. Same as other types of debt, it should be owned and managed.

LLMs are powerful, but they come with costs. Just as we track and manage technical debt, we need to recognize, measure, and pay down our LLM debt. That means asking tough questions before adding LLMs to the stack, and also being bold enough to leverage them where they could provide real value.

If LLM inflation showed us how words can expand and collapse in unhelpful cycles, LLM debt shows us how our systems can quietly accumulate inefficiencies that slow us down. Recognizing it early is the key to keeping our products lean, intelligent, and future-ready.